RMS Titanic

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

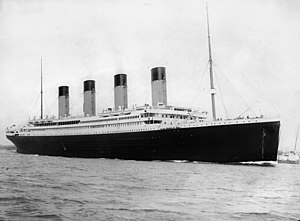

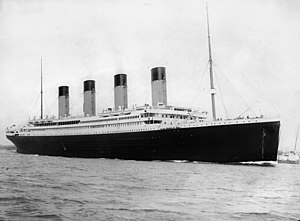

RMS Titanic departing Southampton on 10 April 1912 |

| Career |

|

| Name: |

RMS Titanic |

| Owner: |

White Star Line White Star Line |

| Port of registry: |

Liverpool Liverpool |

| Route: |

Southampton to New York City |

| Ordered: |

17 September 1908 |

| Builder: |

Harland and Wolff, Belfast |

| Yard number: |

401 |

| Laid down: |

31 March 1909 |

| Launched: |

31 May 1911 (not christened) |

| Completed: |

2 April 1912 |

| Maiden voyage: |

10 April 1912 |

| Identification: |

Radio Callsign "MGY" |

| Fate: |

Foundered on 15 April 1912 on its maiden voyage |

| General characteristics |

| Class and type: |

Olympic-class ocean liner |

| Tonnage: |

46,328 GRT |

| Displacement: |

52,310 tons |

| Length: |

882 ft 6 in (269.0 m) |

| Beam: |

92 ft 0 in (28.0 m) |

| Height: |

175 ft (53.3 m) (Keel to top of funnels) |

| Draught: |

34 ft 7 in (10.5 m) |

| Depth: |

64 ft 6 in (19.7 m) |

| Decks: |

9 (A - G) |

| Installed power: |

24 double-ended and 5 single-ended boilers feeding two reciprocating steam engines for the wing propellers and a low-pressure turbine for the center propeller. Effect: 46,000 HP |

| Propulsion: |

Two 3-blade wing propellers and one 4-blade centre propeller |

| Speed: |

Cruising: 21 kn (39 km/h; 24 mph). Max: 24 kn (44 km/h; 28 mph) |

| Capacity: |

Passengers: 2,435, crew: 892 |

| Notes: |

Lifeboats: 20 for 1,178 people |

Her passengers included some of the wealthiest people in the world, such as millionnaires

John Jacob Astor IV,

Benjamin Guggenheim and

Isidor Strauss, as well as over a thousand emigrants from

Ireland,

Scandinavia

and elsewhere seeking a new life in America. The ship was designed to

be the last word in comfort and luxury, with an on-board gymnasium,

swimming pool, libraries, high-class restaurants and opulent cabins. She

also had a powerful wireless telegraph provided for the convenience of

passengers as well as for operational use. Though she had advanced

safety features such as watertight compartments and remotely activated

watertight doors, she lacked enough lifeboats to accommodate all of

those aboard. Due to outdated maritime safety regulations, she carried

only enough lifeboats for 1,178 people – a third of her total passenger

and crew capacity.

After leaving Southampton on 10 April 1912,

Titanic called at

Cherbourg in

France and

Queenstown,

Ireland before heading westwards towards New York. On 14 April 1912,

four days into the crossing and about 375 miles south of Newfoundland,

she hit an iceberg at 11:40 pm (ship's time;

UTC-3). The glancing collision caused

Titanic's hull plates to buckle inwards in a number of locations on her

starboard

side and opened five of her sixteen watertight compartments to the sea.

Over the next two and a half hours, the ship gradually filled with

water and sank. Passengers and some crew members were evacuated in

lifeboats, many of which were launched only partly filled. A

disproportionate number of men – over 90% of those in Second Class –

were left aboard due to a

"women and children first" protocol followed by the officers loading the lifeboats. Just before 2:20 am

Titanic broke up and sank bow-first with over a thousand people still on board. Those in the water died within minutes from

hypothermia caused by immersion in the freezing ocean. The 710 survivors were taken aboard from the lifeboats by the

RMS Carpathia a few hours later.

The disaster was greeted with worldwide shock and outrage at the huge

loss of life and the regulatory and operational failures that had led

to it. Public inquiries in Britain and the United States led to

major improvements in maritime safety. One of their most important legacies was the establishment in 1914 of the

International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea

(SOLAS), which still governs maritime safety today. Many of the

survivors lost all of their money and possessions and were left

destitute; many families, particularly those of crew members from

Southampton, lost their primary bread-winners. They were helped by an

outpouring of public sympathy and charitable donations. Some of the male

survivors, notably the White Star Line's chairman,

J. Bruce Ismay, were accused of cowardice for leaving the ship while women and children were still on board, and they faced social

ostracism.

The

wreck of the Titanic

remains on the seabed, gradually disintegrating at a depth of 12,415

feet (3,784 m). Since its rediscovery in 1985, thousands of artefacts

have been recovered from the sea bed and put on display at museums

around the world.

Titanic has become one of the most famous ships in history, her memory kept alive by numerous

books, films, exhibits and memorials.

Background

Titanic was one the second of the three

Olympic-class ocean liners – the others were the

RMS Olympic and the

RMS Britannic (originally named

Gigantic). They were by far the largest vessels in the White Star Line's fleet, which comprised 29 steamers and tenders in 1912.

The three ships had their genesis in a discussion in mid-1907 between

the White Star Line's chairman, J. Bruce Ismay, and the American

financier

J. Pierpont Morgan, who controlled the White Star Line's parent corporation, the

International Mercantile Marine Co. The White Star Line faced a growing challenge from its main rivals

Cunard, which had just launched

Lusitania and

Mauretania – the fastest passenger ships then in service – and the German lines

Hamburg America and

Norddeutscher Lloyd.

Ismay preferred to compete on size rather than speed and proposed to

commission a new class of liners that would be bigger than anything that

had gone before as well as being the last word in comfort and luxury.

The ships were constructed by the Belfast shipbuilders Harland and

Wolff, who had a long-established relationship with the White Star Line

dating back to 1867.

Harland and Wolff were given a great deal of latitude in designing

ships for the White Star Line; the usual approach was for the latter to

sketch out a general concept which the former would take away and turn

into a ship design. Cost considerations were relatively low on the

agenda and Harland and Wolff was authorised to spend what it needed on

the ships, plus a five per cent profit margin. In the case of the Olympic-class ships, a cost of £3 million for the first two ships was agreed plus "extras to contract" and the usual five per cent fee.

Harland and Wolff put their leading designers to work designing the

Olympic-class vessels. It was overseen by

Lord Pirrie, a director of both Harland and Wolff and the White Star Line;

naval architect Thomas Andrews,

the managing director of Harland and Wolff's design department; Edward

Wilding, Andrews' deputy and responsible for calculating the ship's

design, stability and trim; and

Alexander Carlisle, the shipyard's chief draughtsman and general manager.

Carlisle's responsibilities included the decorations, equipment and all

general arrangements, including the implementation of an efficient

lifeboat davit design.

[a]

On 29 July 1908, Harland and Wolff presented the drawings to J. Bruce

Ismay and other White Star Line executives. Ismay approved the design

and signed three "letters of agreement" two days later authorising the

start of construction. At this point the first ship – which was later to become Olympic – had no name, but was referred to simply as "Number 400", as it was Harland and Wolff's four hundredth hull. Titanic was based on a revised version of the same design and was given the number 401.

Dimensions and layout

Titanic was 882 feet 9 inches (269.06 m) long with a maximum

breadth of 92 feet 6 inches (28.19 m). Her total height, measured from

the base of the keel to the top of the bridge, was 104 feet (32 m). She measured 46,328

gross register tons and with a draught of 34 feet 7 inches (10.54 m), she displaced 52,310 tons.

All three of the Olympic-class ships had eleven decks

(excluding the top of the officers' quarters), eight of which were for

passenger use. From top to bottom, the decks were:

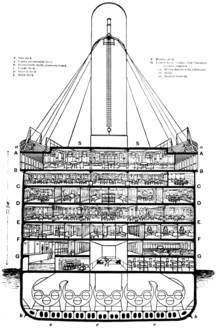

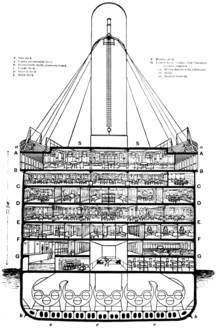

Cutaway diagram of

Titanic's midship section

- The Boat Deck, on which the lifeboats were positioned. It was from here in the early hours of 15 April 1912 that Titanic's

lifeboats were lowered into the North Atlantic. The bridge and

wheelhouse were at the forward end, in front of the captain's and

officers' quarters. The bridge stood 8 feet (2.4 m) above the deck,

extending out to either side so that the ship could be controlled while

docking. The wheelhouse stood directly behind and above the bridge. The

entrance to the First Class Grand Staircase

and gymnasium were located midships along with the raised roof of the

First Class lounge, while at the rear of the deck were the roof of the

First Class smoke room and the relatively modest Second Class entrance.

The wood-covered deck was divided into four segregated promenades; for

officers, First Class passengers, engineers and Second Class passengers

respectively. Lifeboats lined the side of the deck except in the First

Class area, where there was a gap so that the view would not be spoiled.

- A Deck, also called the Promenade Deck, extended along

the entire 546 feet (166 m) length of the superstructure. It was

reserved exclusively for First Class passengers and contained First

Class cabins, the First Class lounge, smoke room, reading and writing

rooms and Palm Court.

- B Deck, the Bridge Deck, was the top weight-bearing

deck and the uppermost level of the hull. More First Class passenger

accommodation was located here with six palatial staterooms (cabins)

featuring their own private promenades. On Titanic, the A La Carte

Restaurant and the Café Parisien provided luxury dining facilities to

First Class passengers. Both were run by subcontracted chefs and their

staff; all were lost in the disaster. The Second Class smoking room and

entrance hall were both located on this deck. The raised forecastle of

the ship was forward of the Bridge Deck, accommodating Number 1 hatch

(the main hatch through to the cargo holds), various pieces of machinery

and the anchor housings. It was kept off-limits to passengers; the

famous "flying" scene at the ship's bow from the 1997 film Titanic

would not have been possible in real life. Aft of the Bridge Deck was

the raised Poop Deck, 106 feet (32 m) long, used as a promenade by Third

Class passengers. It was where many of Titanic's

passengers and crew made their last stand as the ship sank. The

forecastle and Poop Deck were separated from the Bridge Deck by well decks.

- C Deck, the Shelter Deck, was the highest deck to run

uninterrupted from the ships' stem to stern. It included the two well

decks; the aft one served as part of the Third Class promenade. Crew

cabins were located under the forecastle and Third Class public rooms

were situated under the Poop Deck. In between were the majority of First

Class cabins and the Second Class library.

- D Deck, the Saloon Deck, was dominated by three large

public rooms – the First Class Reception Room, the First Class Dining

Saloon and the Second Class Dining Saloon. An open space was provided

for Third Class passengers. First, Second and Third Class passengers had

cabins on this deck, with berths for firemen located in the bow. It was

the highest level reached by the ships' watertight bulkheads (though

only by eight of the fifteen bulkheads).

- E Deck, the Upper Deck, was predominantly used for

passenger accommodation for all classes plus berths for cooks, seamen,

stewards and trimmers. Along its length ran a long passageway nicknamed Scotland Road by the crew, in reference to a famous street in Liverpool.

- F Deck, the Middle Deck, was the last complete deck

and mainly accommodated Third Class passengers. There were also some

Second Class cabins and crew accommodation. The Third Class dining

saloon was located here, as were the swimming pool and Turkish bath.

- G Deck, the Lower Deck, was the lowest complete deck

that carried passengers, and had the lowest portholes, just above the

waterline. The squash court was located here along with the travelling

post office where mail clerks sorted letters and parcels so that they

would be ready for delivery when the ship docked. Food was also stored

here. The deck was interrupted at several points by orlop (partial) decks over the boiler, engine and turbine rooms.

- The Orlop decks and the Tank Top were at the lowest

level of the ship, below the waterline. The orlop decks were used as

cargo space, while the Tank Top – the inner bottom of the ship's hull –

provided the platform on which the ship's boilers, engines, turbines and

electrical generators sat. This part of the ship was dominated by the

engine and boiler rooms, areas that passengers would never normally see.

They were connected with higher levels of the ship by flights of

stairs; twin spiral stairways near the bow gave access up to D Deck.

Features

Engines, boilers and generators

View of the rear port side of

Titanic, showing the rudder and the central and port wing propellers. Note the man at the bottom of the image.

Titanic was equipped with three engines – two

reciprocating four-

cylinder, triple-expansion

steam engines and one centrally placed low-pressure

Parsons turbine – each driving a

propeller. The two reciprocating engines had a combined output of 30,000hp and a further 16,000hp was contributed by the turbine. The White Star Line had previously used the same combination of engines on an earlier liner, the

SS Laurentic, where it had been a great success.

It provided a good combination of performance and speed; reciprocating

engines by themselves were not powerful enough to propel an

Olympic-class

liner at the desired speeds, while turbines were sufficiently powerful

but caused uncomfortable vibrations, a problem that affected the

all-turbine Cunard liners

Lusitania and

Mauretania.

By combining reciprocating engines with a turbine, fuel usage could be

reduced and motive power increased, while using the same amount of

steam.

The two reciprocating engines were giants, each 63 feet (19 m) long

and weighing 720 tons. Their bedplates alone weighed a further 195 tons.

They were powered by steam produced in 29 boilers, 24 of which were

double-ended and 5 single-ended, which contained a total of 159

furnaces.

The boilers were 15 feet 9 inches (4.80 m) in diameter and 20 feet

(6.1 m) long, each weighing 91.5 tons and capable of holding 48.5 tons

of water.

They were heated by burning coal, 6,611 tons of which could be carried in Titanic's

bunkers with a further 1,092 tons in Hold 3. The furnaces required over

600 tons of coal a day to be shovelled into them by hand, requiring the

services of 176 firemen working around the clock. 100 tons of ash a day had to be disposed of by ejecting it into the sea. The work was relentless, dirty and dangerous, and although firemen were paid relatively generously there was a high suicide rate among those who worked in that capacity.

Exhaust steam leaving the reciprocating engines was fed into the

turbine, which was situated aft. From there it passed into a condenser

so that the steam could be condensed back into water and reused.

The engines were attached directly to long shafts which drove the

propellers. There were three, one for each engine; the outer (or wing)

propellers were the largest, each carrying three blades of

manganese-bronze alloy with a total diameter of 23.5 feet (7.2 m). The central propeller was somewhat smaller at 17 feet (5.2 m) in diameter, and could be stopped but not reversed.

Titanic's electrical plant was capable of producing more power than a typical city power station of the time.

Immediately aft of the turbine engine were four 400kW steam-driven

electric generators, used to provide electrical power to the ship, plus

two 30 kW auxiliary generators for emergency use. Their location at the rear of the ship meant that they remained operational until the last few minutes before the ship sank.

Technical facilities

Titanic's rudder was

so huge – at 78 feet 8 inches (23.98 m) high and 15 feet 3 inches

(4.65 m) long, weighing over 100 tons – that it required

steering engines

to move it. Two steam-powered steering engines were installed though

only one was used at any one time, with the other one kept in reserve.

They were connected to the short

tiller through stiff springs, to isolate the steering engines from any shocks in heavy seas or during fast changes of direction. As a last resort, the tiller could be moved by ropes connected to two steam

capstans. The capstans were also used to raise and lower the ship's five anchors (one port, one starboard, one in the centreline and two

kedging anchors).

The ship was equipped with its own waterworks, capable of heating and

pumping water to all parts of the vessel via a complex network of pipes

and valves. The main water supply was taken aboard while Titanic

was in port but in an emergency she could also distil fresh water from

the sea, though this was not a straightforward process as the

distillation plant was quickly clogged by salt deposits. A network of

insulated ducts conveyed warm air, driven by electric fans, around the

ship, and First Class cabins were fitted with additional electric

heaters.

Titanic was equipped with two 1.5 kW

spark-gap wireless telegraphs

located in the radio room on the Bridge Deck. One set was used for

transmitting messages and the other, located in a soundproofed booth,

for receiving them. The signals were transmitted through two parallel

wires strung between the ship's masts, 50 feet (15 m) above the funnels

to avoid the corrosive smoke. The system was one of the most powerful in the world, with a range of up to 1,000 miles. It was owned and operated by the

Marconi Company

rather than the White Star Line, and was intended primarily for

passengers rather than ship operations. The function of the two wireless

operators – both Marconi employees – was to operate a 24-hour service

sending and receiving wireless telegrams for passengers. They did,

however, also pass on professional ship messages such as weather reports

and ice warnings.

Passenger facilities

The passenger facilities aboard

Titanic aimed to meet the

highest standards of luxury. The ship could accommodate 739 First Class

passengers, 674 in Second Class and 1,026 in Third Class. Her crew

numbered about 900 people; in all, she could carry total of about

3,339 people. Her interior design was a departure from that of other

passenger liners, which had typically been decorated in the rather heavy

style of a

manor house or an

English country house.

Titanic was laid out in a much lighter style similar to that of contemporary high-class hotels – the

Ritz Hotel was a reference point – with First Class cabins finished in the

Empire style. A variety of other decorative styles, ranging from the

Renaissance to

Victorian style,

were used to decorate cabins and public rooms in First and Second Class

areas of the ship. The aim was to convey an impression that the

passengers were in a floating hotel rather than a ship; as one passenger

recalled, on entering the ship's interior a passenger would "at once

lose the feeling that we are on board ship, and seem instead to be

entering the hall of a some great house on shore."

There was a telephone system, a lending library and a large barber shop on the ship. The First Class section had a swimming pool, a gymnasium,

squash court,

Turkish bath,

electric bath and a Verandah Cafe.

First Class common rooms were adorned with ornate wood panelling,

expensive furniture and other decorations while the Third Class general

room had pine panelling and sturdy teak furniture.

[54] The

Café Parisien offered the best French

haute cuisine for the First Class passengers, who sat on a sunlit veranda fitted with trellis decorations.

[55]

| Titanic's First Class passenger facilities |

|

|

|

Titanic's gymnasium on the Boat Deck, which was equipped with the latest exercise machines.

|

|

|

|

Titanic's famous Grand Staircase, which provided access between the Boat Deck and D Deck.

|

|

|

|

The A La Carte restaurant on B Deck, run as a concession by Italian-born chef Gaspare Gatti.

|

|

Third Class passengers were not treated as luxuriously as those in

First Class, but even so they were better off than their counterparts on

many other ships of the time. They were accommodated in cabins

accommodating between two and ten people, with a further 164 open berths

provided for single young men on G Deck.

They were, however, much more limited in their washing and bathing

facilities. There were only two bathrooms, one each for men and women,

for the entire Third Class complement. They had to wash their own

clothes in washrooms equipped with iron tubs, whereas those travelling

in First and Second Class could use the ship's laundry.

There were also restrictions on which parts of the ship they could

enter; all three classes were segregated from each other, and although

in theory passengers from the higher classes could visit the lower-class

areas of the ship, in practice respect for social conventions meant

that they did not do so.

Leisure facilities were provided for all three classes to pass the

time. As well as making use of the indoor amenities such as the library,

smoking-rooms and gymnasium, it was also customary for passengers to

socialise on the open deck, promenading or relaxing in hired deck chairs

or wooden benches. A passenger list was published before the sailing to

inform the public which members of the great and good were on board,

and it was not uncommon for ambitious mothers to use the list to

identify rich bachelors to whom they could introduce their marriageable

daughters during the voyage.

One of

Titanic's most distinctive features was its First Class staircase, known as the

Grand Staircase

or Grand Stairway. This descended through five decks of the ship, from

the Boat Deck to the Reception Room adjoining the First Class Dining

Saloon on D Deck.

It was capped with a dome of wrought iron and glass that admitted

natural light. Each landing off the staircase gave access to ornate

entrance halls lit by gold-plated light fixtures.

At the uppermost landing was a large carved wooden panel containing a

clock, with figures of "Honour and Glory Crowning Time" flanking the

clock face. The Grand Staircase was destroyed in

Titanic's sinking and is now just a void in the ship which modern explorers have used to access the lower decks. During the filming of

James Cameron's

Titanic

in 1997, his replica of the Grand Staircase was ripped from its

foundations by the force of the inrushing water on the set. It has been

suggested that during the real event, the entire Grand Staircase was

ejected upwards through the dome.

Mail and cargo

Although

Titanic was primarily a passenger liner, she also carried a substantial amount of cargo. Her designation as a

Royal Mail Ship indicated that she carried mail under contract with the

Royal Mail (and also for the

United States Postal Service). 26,800 cubic feet (760 m

3) of space in her holds was allocated for the storage of letters, parcels and

specie,

(bullion, coins and other valuables). The Sea Post Office on G Deck was

manned by five postal clerks, three Americans and two Britons, who

worked thirteen hours a day, seven days a week sorting up to 60,000

items daily.

The ship's passengers brought with them a huge amount of baggage; another 19,455 cubic feet (550.9 m

3)

was taken up by first- and second-class baggage. In addition, there was

a considerable quantity of regular cargo, ranging from furniture to

foodstuffs and even motor cars. Despite later myths, the cargo on

Titanic's maiden voyage was fairly mundane; there was no gold,

exotic minerals or diamonds, and one of the more famous items lost in the shipwreck, a jewelled copy of the

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, was valued at only £405 (£29,717 today) – hardly the stuff of legends.

Titanic

was equipped with eight electric cranes, four electric winches and

three steam winches to lift cargo and baggage in and out of the hold.

Lifeboats

Titanic carried a total of 20 lifeboats: 14 standard wooden

Harland and Wolff lifeboats with a capacity of 65 people each and four

Englehardt "collapsible" lifeboats (identified as A to D) with a

capacity of 47 people each. In addition, she had two emergency

cutters with a capacity of 40 people each.

[b] All of the lifeboats were stowed securely on the boat deck and, except for A and B, connected to

davits

by ropes.Those on the starboard side were odd-numbered 1–15 from bow to

stern, while those on the port side were even-numbered 2–16 from bow to

stern. The two cutters were kept swung out, hanging from the davits,

ready for immediate use, while collapsible lifeboats C and D were stowed

on the boat deck (connected to davits) immediately inboard of boats 1

and 2 respectively. Collapsible lifeboats A and B were stored on the

roof of the officers' quarters, on either side of number 1 funnel. There

were no davits to lower them and their weight would make them

challenging to launch.

Each boat carried (among other things) food, water, blankets, and a

spare lifebelt. Lifeline ropes on the boats' sides enabled them to save

additional people from the water if necessary.

Titanic had 16 sets of davits, each able to handle 4 lifeboats. This gave

Titanic the ability to carry up to 64 wooden lifeboats

[67],

which would have been enough for 4,000 people – considerably more than

her actual capacity. However, the White Star Line decided that only 16

wooden lifeboats and four collapsibles

[c] would be carried, which could accommodate 1,178 people, only one-third of

Titanic's total capacity.

[d]

At the time, the Board of Trade's regulations required British vessels

over 10,000 tons to carry 16 lifeboats with a capacity of 5,500 cubic

feet (160 m

3), plus enough capacity in rafts and floats for

75% (50% for vessels with watertight bulkheads) of that in the

lifeboats. In principle, the White Star Line could even have made use of

the exception for vessels with watertight bulkheads, which would have

reduced the legal requirements to a capacity of 756 persons only.

[69] Therefore, the White Star Line actually provided much more lifeboat accommodation than was legally required.

[e]

Building and preparing the ship

Construction, launch and fitting-out

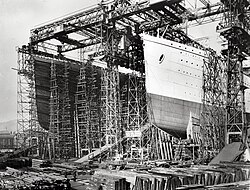

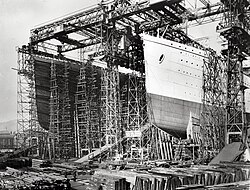

Titanic and

Olympic under construction in Belfast

The sheer size of

Titanic and her sister ships posed a major

engineering challenge for Harland and Wolff; no shipbuilder had ever

before attempted to construct vessels of this size. The ships were

constructed on Queen's Island, now known as the

Titanic Quarter, in

Belfast Harbour. Harland and Wolff had to demolish three existing slipways and build two new

slipways, the biggest ever constructed up to that time, to accommodate the giant ships.

Their construction was facilitated by an enormous gantry built by

Sir William Arrol & Co., a Scottish firm responsible for the building of the

Forth Bridge and London's

Tower Bridge.

The Arrol Gantry stood 228 feet (69 m) high, was 270 feet (82 m) wide

and 840 feet (260 m) long, and weighed more than 6,000 tons. It

accommodated a number of mobile cranes and a separate floating crane,

capable of lifting 200 tons, was brought in from Germany.

The construction of

Titanic and

Olympic took place virtually in parallel, with

Olympic's hull laid down first on 16 December 1908 and

Titanic's on 31 March 1909.

Both ships took about 26 months to build and followed much the same

construction process. They were designed essentially as an enormous

floating

box girder, with the

keel

acting as a backbone and the frames of the hull forming the ribs. At

the base of the ships, a double bottom 5 feet 3 inches (1.60 m) deep

supported 300 frames, each between 24 inches (61 cm) and 36 inches

(91 cm) apart and measuring up to about 66 feet (20 m) long. They

terminated at the bridge deck (B Deck) and were covered with steel

plates which formed the outer skin of the ships.

The 2,000 hull plates were single pieces of rolled steel, mostly up

to 6 feet (1.8 m) wide and 30 feet (9.1 m) long and weighing between 2.5

and 3 tons. Their thickness varied from 1.5 inches (3.8 cm) to 1 inch (2.5 cm). The plates were laid in a

clinkered (overlapping) fashion from the keel to the bilge. Above that point they were laid in the "in and out" fashion, where

strake plating was applied in bands (the "in strakes") with the gaps covered by the "out strakes", overlapping on the edges.

Steel welding was still in its infancy, so the structure was held together with over three million iron and steel

rivets which by themselves weighed over 1,200 tons. These were fitted using hydraulic machines or were hammered in by hand.

The interiors of the

Olympic-class ships were subdivided into

sixteen primary compartments divided by fifteen bulkheads which extended

well above the waterline. Eleven vertically closing watertight doors

could seal off the compartments in the event of an emergency. The ships' exposed decking was made of pine and teak, while interior ceilings were covered in painted granulated

cork to combat condensation.

The superstructure consisted of two decks, the Promenade Deck and Boat

Deck, which were some 500 feet (150 m) long. They accommodated the

officers' quarters, gymnasium, public rooms and first-class cabins, plus

the bridge and wheelhouse. The ships' lifeboats were carried on the

Boat Deck, the uppermost deck.

Standing above the decks were four funnels, though only three were

functional – the last one was a dummy, installed for aesthetic purposes –

and two masts, each 155 feet (47 m) high, which supported derricks for

loading cargo. A wireless aerial was slung between the masts.

The work of constructing the ships was difficult and dangerous. For the 15,000 men who worked at Harland and Wolff at the time,

safety precautions were rudimentary at best; a lot of the work was

dangerous and was carried out without any safety equipment like hard

hats or hand guards on machinery. As a result, deaths and injuries were

to be expected. During Titanic's

construction, 246 injuries were recorded, 28 of them "severe", such as

arms severed by machines or legs crushed under falling pieces of steel.

Six people died on the ship itself while it was being constructed and

fitted out and another two died in the shipyard workshops and sheds.

Titanic was launched at 12:15 pm on 31 May 1911 in the

presence of Lord Pirrie, J. Pierpoint Morgan and J. Bruce Ismay and

100,000 onlookers. 22 tons of soap and tallow were spread on the slipway to lubricate the ship's passage into the

River Lagan. In keeping with the White Star Line's traditional policy, the ship was not formally named or christened with champagne. Just before the launch a worker was killed when a piece of wood fell on him.

The ship was towed to a fitting-out berth where, over the course of the

next year, her engines, funnels and superstructure were installed and

her interior was fitted out.

The work took longer than expected due to design changes ordered by

Ismay and a temporary pause in work occasioned by the need to repair

Olympic, which had been in a collision in September 1911. Had

Titanic been finished earlier, she might well have missed her rendezvous with an iceberg.

Sea trials

Titanic's sea trials began at 6 am on Monday, 2 April 1912,

just two days after her fitting out was finished and eight days before

she was due to leave Southampton on her maiden voyage. The trials had been delayed for a day due to bad weather, but by Monday morning it was clear and fair.

Aboard were 78 stokers, greasers and firemen, and 41 members of crew.

No domestic staff appear to have been aboard. Representatives of various

companies travelled on

Titanic's

sea trials, Thomas Andrews and Edward Wilding of Harland and Wolff and

Harold A. Sanderson of IMM. Bruce Ismay and Lord Pirrie were too ill to

attend.

Jack Phillips and

Harold Bride

served as radio operators, and performed fine-tuning of the Marconi

equipment. Francis Carruthers, a surveyor from the Board of Trade, was

also present to see that everything worked, and that the ship was fit to

carry passengers.

[86]

The sea trials consisted of a number of tests of her handling characteristics, carried out first in

Belfast Lough and then in the open waters of the

Irish Sea. Over the course of about twelve hours,

Titanic

was driven at different speeds, her turning ability was tested and a

"crash stop" was performed in which the engines were reversed full ahead

to full astern, bringing her to a stop in 850 yd (777 m) or 3 minutes

and 15 seconds.

The ship covered a distance of about 80 miles (130 km), averaging 18

knots (21 mph; 33 km/h) and reaching a maximum speed of just under 21

knots (24 mph; 39 km/h).

On returning to Belfast at about 7 pm, the surveyor signed an

"Agreement and Account of Voyages and Crew", valid for twelve months,

which declared the ship seaworthy. An hour later,

Titanic left

Belfast again – as it turned out, for the last time – to head to

Southampton, a voyage of some 570 miles (920 km). She arrived there at

about midnight and was towed to the port's Berth 44, ready for the

arrival of her passengers and the remainder of her crew.

Maiden voyage

Titanic was only to sail as a complete ship for two weeks before she sank; although she was registered at

Liverpool, she never made it to her home port. The story of her sinking is famous, but will only be covered briefly here.

Crew

Titanic had around 885 crew members on board for her maiden voyage.

Like other vessels of her time, she did not have a permanent crew, and

the vast majority of crew members were casual workers who only came

aboard the ship a few hours before she sailed from Southampton.

The process of signing up recruits had begun on 23 March and some had

been sent to Belfast, where they served as a skeleton crew during Titanic's sea trials and passage to England at the start of April.

Captain

Edward John Smith, the most senior of the White Star Line's captains, was transferred from

Olympic to take command of

Titanic.

Henry Tingle Wilde also came across from

Olympic to take the post of

Chief Mate.

Titanic's previously designated Chief Mate and First Officer,

William McMaster Murdoch and

Charles Lightoller, were bumped down to the ranks of First and Second Officer respectively. The original Second Officer,

David Blair,

was dropped altogether. He expressed deep disappointment about the

decision before the voyage, but was presumably greatly relieved

afterwards.

Titanic's crew were divided into three principal departments: Deck, with 66 crew; Engine, with 325; and Victualling, with 494.

The vast majority of the crew were thus not seamen, but were either

engineers, firemen or stokers, responsible for looking after the

engines, or stewards and galley staff, responsible for the passengers. Of these, over 97% were male; just 23 of the crew were female, mainly stewardesses.

The rest represented a great variety of professions – bakers, chefs,

butchers, fishmongers, dishwashers, stewards, gymnasium instructors,

laundrymen, waiters, bed-makers, cleaners and even a printer, who produced a daily newspaper for passengers called the Atlantic Daily Bulletin with the latest news received by the ship's wireless operators. Titanic

also had a ship's cat, Jenny, who gave birth to a litter of kittens

shortly before the ship's maiden voyage; all perished in the sinking.

Most of the crew signed on in Southampton on 6 April; in all, 699 of the crew came from there, and 40 per cent were natives of the town.

A few specialist staff were self-employed or were subcontractors. These

included the five postal clerks, who worked for the Royal Mail and US

Postal Service, the staff of the First Class

A La Carte

Restaurant and the Café Parisien, the radio operators (who were employed

by Marconi) and the eight musicians, who were employed by an agency and

travelled as second-class passengers. Crew pay varied greatly, from Captain Smith's £105 a month (equivalent to £7,704 today) to the £3 10

s

(£257 today) that stewardesses earned. The lower-paid victualling staff

could, however, supplement their wages substantially through tips from

passengers.

Passengers

Titanic's passengers

numbered around 1,317 people: 324 in First Class, 284 in Second Class

and 709 in Third Class. 869 (66%) were male and 447 (34%) female. There

were 107 children in all, the largest number of which were in Third

Class.

The ship was considerably under capacity on her maiden voyage, as she

could accommodate 2,566 passengers – 1,034 First Class, 510 Second Class

and 1,022 Third Class.

Some of the most prominent people of the day booked a passage aboard

Titanic, travelling in First Class. Among them were the American millionaire

John Jacob Astor IV and his wife

Madeleine Force Astor, industrialist

Benjamin Guggenheim,

Macy's owner

Isidor Straus and his wife

Ida,

Denver millionairess

Margaret "Molly" Brown,

[f] Sir

Cosmo Duff Gordon and his wife,

couturière Lucy (Lady Duff-Gordon), cricketer and businessman

John Borland Thayer with his wife Marian together with their son

Jack, the

Countess of Rothes, author and socialite

Helen Churchill Candee, journalist and social reformer

William Thomas Stead, author

Jacques Futrelle with his wife May, and silent film actress

Dorothy Gibson, among others.

[103] Titanic's owner J. P. Morgan was scheduled to travel on the maiden voyage, but cancelled at the last minute. Also aboard the ship were the White Star Line's managing director J. Bruce Ismay and

Titanic's designer Thomas Andrews, who was on board to observe any problems and assess the general performance of the new ship.

The passengers began arriving from 9.30 am, when the

London and South Western Railway's boat train from

London Waterloo station reached

Southampton Terminus railway station on the quayside, right alongside

Titanic's berth.

The large number of Third Class passengers meant that they were the

first to board, with First and Second Class passengers following up to

within an hour of departure. Stewards showed them to their cabins and

First Class passengers were personally greeted by Captain Smith on

boarding.

Third Class passengers were inspected for ailments and physical

impairments that might lead to them being refused entry to the United

States – not a prospect that the White Star Line wished to see, as it

would have to carry them back across the Atlantic. Not all of those who had booked tickets made it to the ship; about fifty people cancelled for various reasons, and not all of those who boarded stayed aboard for the entire journey.

Fares aboard

Titanic varied enormously in cost. Third Class fares from London, Southampton or Queenstown cost £7 5

s (equivalent to £532 today) while the cheapest First Class fares cost £23 (£1,688 today).

[109] The most expensive First Class suites cost up to £870 in high season (£63,837 today).

Departure and westbound journey

Titanic's maiden

voyage was intended to be the first of many cross-Atlantic journeys

between Southampton in England, Cherbourg in France, Queenstown in

Ireland and New York in the United States, returning via

Plymouth in England on the eastbound leg. The White Star Line intended to operate three ships on that route:

Titanic,

Olympic and the smaller

RMS Oceanic.

Each would sail once every three weeks from Southampton and New York,

usually leaving at noon each Wednesday from Southampton and each

Saturday from New York, thus enabling the White Star Line to offer

weekly sailings in each direction. Special trains were scheduled from

London and Paris to convey passengers to Southampton and Cherbourg

respectively.

[109]

The maiden voyage began on time at noon on Wednesday 10 April 1912 but nearly ended in disaster only a few minutes later. As

Titanic passed the moored liners

SS City of New York and

Oceanic, her huge displacement caused both of the smaller ships to be lifted by a bulge of water, then dropped into a trough.

New York's mooring cables could not take the sudden strain and snapped, swinging her round stern-first towards

Titanic. A nearby tugboat,

Vulcan, came to the rescue by taking

New York under tow and Captain Smith ordered

Titanic's engines to be put "full astern". The two ships only avoided a collision by a matter of about 4 feet (1.2 m). The incident delayed

Titanic's departure for about an hour while the drifting

New York was brought under control.

After making it safely through the complex tides and channels of

Southampton Water and the

Solent,

Titanic headed out into the

English Channel. She headed for the French port of Cherbourg, a journey of 77 nautical miles (89 mi; 143 km). The weather was windy, very fine but cold and overcast. Because Cherbourg lacked docking facilities for a ship the size of

Titanic,

tenders had to be used to transfer passengers from shore to ship. The White Star Line operated two at Cherbourg, the

SS Traffic and the

SS Nomadic. Both had been designed specifically as tenders for the Olympic-class liners and were launched shortly after

Titanic. (

Nomadic is today the only White Star Line ship still afloat.) Four hours after

Titanic left Southampton, she arrived at Cherbourg and was met by the tenders. 274 more passengers boarded

Titanic and 24 left aboard the tenders to be conveyed to shore. The process was completed within only 90 minutes and at 8 pm

Titanic weighed anchor and left for Queenstown with the weather continuing cold and windy.

At 11.30 am on Thursday 11 April,

Titanic arrived at Cork Harbour in southern Ireland. It was a partly cloudy but relatively warm day with a brisk wind.

Again, the dock facilities were not suitable for a ship of her size,

and tenders were used to bring passengers aboard. 113 Third Class and

seven Second Class passengers came aboard, while seven passengers left.

Among the departures was Father

Francis Browne, a

Jesuit trainee, who was a keen photographer and took many photographs aboard

Titanic,

including the last-ever known photograph of the ship. A decidedly

unofficial departure was that of a crew member, stoker John Coffey, a

native of Queenstown who sneaked off the ship by hiding under mail bags

being transported to shore.

Titanic weighed anchor for the last time at 1.30 pm and departed on her westward journey across the Atlantic.

The route of

Titanic's maiden voyage, with the coordinates of her sinking.

After leaving Queenstown

Titanic followed the Irish coast as far as

Fastnet Rock,

a distance of some 55 nautical miles (63 mi; 102 km). From there she

travelled 1,620 nautical miles (1,860 mi; 3,000 km) along a

Great Circle

route across the North Atlantic to reach a spot in the ocean known as

"the corner" south-east of Newfoundland, where westbound steamers

carried out a change of course. The next leg of her journey would take

her a further 1,023 nautical miles (1,177 mi; 1,895 km) from the corner

along a

rhumb line course to

Nantucket Shoals Light. A final leg of 193 nautical miles (222 mi; 357 km) would bring the ship to

Ambrose Light and finally to

New York Harbor.

Titanic only sailed a few hours past the corner before she made her fatal rendezvous with an iceberg.

The next three days passed without incident. From 11 April to

local apparent noon the next day,

Titanic

covered 484 nautical miles (557 mi; 896 km); the following day, 519

nautical miles (597 mi; 961 km); and by noon on the final day of her

voyage, 546 nautical miles (628 mi; 1,011 km). From then until the time

of her sinking she travelled another 258 nautical miles (297 mi;

478 km), averaging about 21 knots (24 mph; 39 km/h).

The weather cleared as she left Ireland under cloudy skies with a

headwind. Temperatures remained fairly mild through Saturday 13 April,

but the following day

Titanic crossed a cold

weather front

with strong winds and waves of up to 8 feet (2.4 m). These died down as

the day progressed until, by the evening of Sunday 14 April, it became

clear, calm and very cold.

Titanic received a series of warnings from other ships of drifting ice in the area of the

Grand Banks of Newfoundland. Nonetheless the ship continued to steam at full speed, which was standard practice at the time.

It was generally believed that ice posed little danger to large vessels

and Captain Smith himself had declared that he could not "imagine any

condition which would cause a ship to founder. Modern shipbuilding has

gone beyond that."

Sinking

At 11.40 pm (ship's time), lookout

Frederick Fleet spotted an iceberg immediately ahead of

Titanic and alerted the bridge.

First Officer William Murdoch ordered the ship to be steered around the obstacle and the engines to be put in reverse, but it was too late; the starboard side of

Titanic

struck the iceberg, creating a series of holes below the waterline.

Five of the ship's watertight compartments were breached. It soon became

clear that the ship was doomed, as she could not survive more than four

compartments being flooded.

Titanic began sinking bow-first, with water spilling from compartment to compartment as her angle in the water became steeper.

Those aboard Titanic were ill-prepared for such an emergency.

There was only enough space in the lifeboats for a third of her maximum

number of passengers and crew,

and the crew had not been trained adequately in carrying out an

evacuation. The officers did not know how many they could safely put

aboard the lifeboats and launched many of them barely half-full.

Third-class passengers were largely left to fend for themselves,

causing many of them to become trapped below decks as the ship filled

with water. A "women and children first" protocol was generally followed for the loading of the lifeboats and most of the male passengers and crew were left aboard.

Two hours and forty minutes after Titanic struck the iceberg,

her rate of sinking suddenly increased as her forward deck dipped

underwater and the sea poured in through open hatches and grates.

As her unsupported stern rose out of the water, exposing the

propellers, the ship split apart between the third and fourth funnels

due to the immense strain on the keel.

The severed bow section headed for the sea bed, while the stern

remained afloat for a few minutes longer, rising to a nearly vertical

angle with hundreds of people still clinging to it.

At 2.20 am, the stern sank, pitching the remaining passengers and crew

into lethally cold water with a temperature of only 28 °F (-2 °C).

Almost all of those in the water died of hypothermia or cardiac arrest

within minutes. Only 13 of them were helped into the lifeboats though these had room for almost 500 more occupants.

Distress signals were sent by wireless, rockets and lamp, but none of

the ships that responded were near enough to reach her before she sank. A nearby ship, the Californian, which was the last to have been in contact with her before the collision, saw her flares but failed to assist. Around 4 am, RMS Carpathia arrived on the scene in response to Titanic's earlier distress calls. 710 people survived the disaster and were conveyed by Carpathia to New York, Titanic's

original destination. 1,517 people were lost, either drowning inside

the sinking ship or freezing to death on the surface (kept from drowning

by their lifebelts).

Aftermath of sinking

Homecoming of the survivors

According to an eyewitness report, there "were many pathetic scenes" when

Titanic's survivors disembarked at New York

Carpathia took three days to reach New York after leaving the

scene of the disaster. Her journey was slowed by pack ice, fog,

thunderstorms and rough seas.

She was, however, able to pass news to the outside world by wireless

about what had happened. The initial reports were confused, leading the

American press to report erroneously on 15 April that

Titanic was being towed to port by the

SS Virginian.

Later that day, confirmation came through that

Titanic had

been lost and that most of her passengers and crew had died. The news

attracted crowds of people to the White Star Line's offices in London,

New York, Southampton, Liverpool and Belfast. It hit hardest in

Southampton, whose people suffered the greatest losses from the sinking.

According to the

Hampshire Chronicle on 20 April 1912, almost

1,000 local families were directly affected. Almost every street in the

Chapel district of the town lost more than one resident and over

500 households lost a member.

[141]

The British Army's newspaper, The War Cry, reported that "none

but a heart of stone would be unmoved in the presence of such anguish.

Night and day that crowd of pale, anxious faces had been waiting

patiently for the news that did not come. Nearly every one in the crowd

had lost a relative." It was not until 17 April that the first incomplete lists of survivors came through, delayed by poor communications.

Carpathia docked at 9.30 pm on 18 April at New York's

Pier 54

and was greeted by some 40,000 people waiting at the quayside in heavy

rain. Immediate relief in the form of clothing and transportation to

shelters was provided by the Women's Relief Committee, the

Travelers Aid Society of New York, and the

Council of Jewish Women, among other organisations.

[145][146] Many of

Titanic's

surviving passengers did not linger in New York but headed onwards

immediately to relatives' homes. Some of the wealthier survivors

chartered private trains to take them home, and the

Pennsylvania Railroad laid on a special train free of charge to take survivors to

Philadelphia.

Titanic's 214 surviving crew members were taken to the

Red Star Line's steamer

SS Lapland, where they were accommodated in passenger cabins.

Carpathia was hurriedly restocked with food and provisions before resuming her journey to

Fiume,

Austria-Hungary. Her crew were given a bonus of a month's wages by Cunard as a reward for their actions, and some of

Titanic's passengers joined together to give them an additional bonus of nearly £900 (£66,038 today), divided between the crew members.

The ship's arrival in New York led to a frenzy of press interest,

with newspapers competing to be the first to report the survivors'

stories. Some reporters bribed their way aboard the

pilot boat New York, which guided

Carpathia into harbour, and one even managed to get onto

Carpathia before she docked. Crowds gathered outside newspaper offices to see the latest reports being posted in the windows or on billboards.

It took another four days for a complete list of casualties to be

compiled and released, adding to the agony of relatives waiting for news

of those who had been aboard

Titanic. On 23 April, the

Daily Mail reported:

Late in the afternoon hope died out. The waiting

crowds thinned, and silent men and women sought their homes. In the

humbler homes of Southampton there is scarcely a family who has not lost

a relative or friend. Children returning from school appreciated

something of tragedy, and woeful little faces were turned to the

darkened, fatherless homes.

Many charities were set up to help the victims and their families,

many of whom lost their sole breadwinner, or, in the case of many Third

Class survivors, everything they owned. On 29 April opera stars

Enrico Caruso and

Mary Garden and members of the

Metropolitan Opera

raised $12,000 in benefits for victims of the disaster by giving

special concerts in which versions of "Autumn" and "Nearer My God To

Thee" were part of the program.

[152] In Britain, relief funds were organised for the families of

Titanic's lost crew members, raising nearly £450,000 (£33,018,954 today). One such fund was still in operation as late as the 1960s.

Investigations into the disaster

"The Margin of Safety Is Too Narrow!", a 1912 cartoon by Kyle Fergus,

showing the public demanding answers from the shipping companies

Even before the survivors arrived in New York, investigations were

being planned to discover what had happened, and what could be done to

prevent a recurrence. The

United States Senate initiated an inquiry into the disaster on 19 April, a day after

Carpathia arrived in New York.

[154]

The chairman of the inquiry, Senator

William Alden Smith,

wanted to gather accounts from passengers and crew while the events

were still fresh in their minds. Smith also needed to subpoena all

surviving British passengers and crew while they were still on American

soil, which prevented them from returning to the UK before the American

inquiry was completed on 25 May.

[154]

The British press condemned Smith as an opportunist, insensitively

forcing an inquiry as a means of gaining political prestige and seizing

"his moment to stand on the world stage". Smith, however, already had a

reputation as a campaigner for safety on U.S. railroads, and wanted to

investigate any possible malpractices by railroad tycoon

J. P. Morgan,

Titanic's ultimate owner.

Lord Mersey was appointed to head the

British Board of Trade's

inquiry into the disaster, which took place between 2 May and 3 July.

Each inquiry took testimony from both passengers and crew of

Titanic, crew members of Leyland Line's

Californian, Captain

Arthur Rostron of

Carpathia and other experts.

The two inquiries reached broadly similar conclusions; the regulations

on the number of lifeboats that ships had to carry were out of date and

inadequate, Captain Smith had failed to take proper heed of ice warnings,

the lifeboats had not been properly filled or crewed, and the collision

was the direct result of steaming into a danger area at too high a

speed.

The recommendations included major changes in maritime regulations to

implement new safety measures, such as ensuring that more lifeboats

were provided, that lifeboat drills were properly carried out and that

wireless equipment on passenger ships was manned around the clock. An

International Ice Patrol

was set up to monitor the presence of icebergs in the North Atlantic,

and maritime safety regulations were harmonised internationally through

the

International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea; both measures are still in force today.

Role of the SS Californian

SS

Californian, which had tried to warn

Titanic of the danger from pack-ice

One of the most controversial issues examined by the inquiries was the role played by the

SS Californian, which had been only a few miles from

Titanic

but had not picked up her distress calls or responded to her signal

rockets. Testimony before the British inquiry revealed that at 10:10 pm,

Californian observed the lights of a ship to the south; it was later agreed between Captain

Stanley Lord and Third Officer C.V. Groves (who had relieved Lord of duty at 11:10 pm) that this was a passenger liner.

Californian had warned the ship by radio of the pack ice which was the reason

Californian had stopped for the night, but was rebuked by

Titanic's senior wireless operator,

Jack Phillips.

At 11:50 pm, the officer had watched that ship's lights flash out, as

if it had shut down or turned sharply, and that the port light was now

visible. Morse light signals to the ship, upon Lord's order, occurred

five times between 11:30 pm and 1:00 am, but were not acknowledged. (In

testimony, it was stated that

Californian's morse lamp had a range of about four miles (6 km), so could not have been seen from

Titanic.)

[161]

Captain Lord had retired at 11:30 pm; however, Second Officer Herbert

Stone, now on duty, notified Lord at 1:15 am that the ship had fired a

rocket, followed by four more. Lord wanted to know if they were company

signals, that is, coloured flares used for identification. Stone said

that he did not know and that the rockets were all white. Captain Lord

instructed the crew to continue to signal the other vessel with the

morse lamp, and went back to sleep. Three more rockets were observed at

1:50 am and Stone noted that the ship looked strange in the water, as if

she were listing. At 2:15 am, Lord was notified that the ship could no

longer be seen. Lord asked again if the lights had had any colours in

them, and he was informed that they were all white.

[162]

Californian eventually responded. At 5:30 am, Chief Officer George Stewart awakened wireless operator

Cyril Furmstone Evans, informed him that rockets had been seen during the night, and asked that he try to communicate with any ships.

Frankfurt notified the operator of

Titanic's loss, Captain Lord was notified, and the ship set out to render assistance. It arrived well after

Carpathia had already picked up all the survivors.

[162]

The inquiries found that

Californian was much closer to

Titanic

than the 19.5 miles (31.4 km) that Captain Lord had believed, and that

Lord should have awakened the wireless operator after the rockets were

first reported to him, and thus could have acted to prevent loss of

life.

[161][g]

Survivors and victims

Of a total of 2,224 people aboard Titanic only 710, less than a third, survived and 1,514 perished.

Second and Third Class passengers were least likely to survive. The

highest survival rates were among women and children in First Class. The

table below shows the survivors and victims for passengers and crew

onboard the RMS Titanic. Passengers are subdivided into men, women and children for each class while crew is divided into men and women.

Retrieval and burial of the dead

Once the massive loss of life became known, White Star Line chartered the cable ship CS

Mackay-Bennett from

Halifax, Nova Scotia to retrieve bodies. Three other Canadian ships followed in the search: the cable ship

Minia, lighthouse supply ship

Montmagny and sealing vessel

Algerine.

Each ship left with embalming supplies, undertakers, and clergy. Of the

333 victims that were eventually recovered, 328 were retrieved by the

Canadian ships and five more by passing North Atlantic steamships.

[h] In mid-May 1912,

RMS Oceanic

recovered three bodies over 200 miles (320 km) from the site of the

sinking who were among the original occupants of Collapsible A. When

Fifth Officer

Harold Lowe

and six crewmen returned to the wreck site sometime after the sinking

in a lifeboat to pick up survivors, they had rescued a female from

Collapsible A, but left the dead bodies of three of its occupants.

[i] After their retrieval from Collapsible A by

Oceanic, the bodies were then buried at sea.

The first body recovery ship to reach the site of the sinking, the cable ship CS

Mackay-Bennett

found so many bodies that the embalming supplies aboard were quickly

exhausted, and health regulations required that only embalmed bodies

could be returned to port.

[171] Captain Larnder of the

Mackay-Bennett

and undertakers aboard decided to preserve only the bodies of first

class passengers, justifying their decision by the need to visually

identify wealthy men to resolve any disputes over large estates. As a

result, third class passengers and crew were buried at sea. Larnder

himself claimed that as a mariner, he would expect to be buried at sea.

[172]

Bodies recovered were preserved for transport to Halifax, the closest

city to the sinking with direct rail and steamship connections. The

Halifax coroner, John Henry Barnstead, developed a detailed system to

identify bodies and safeguard personal possessions. Relatives from

across North America came to identify and claim bodies. A large

temporary morgue was set up in a

curling rink and undertakers were called in from all across Eastern Canada to assist.

[172]

Some bodies were shipped to be buried in their home towns across North

America and Europe. About two-thirds of the bodies were identified.

Unidentified victims were buried with simple numbers based on the order

in which their bodies were discovered. The majority of recovered

victims, 150 bodies, were buried in three Halifax cemeteries, the

largest being

Fairview Lawn Cemetery followed by the nearby

Mount Olivet and

Baron de Hirsch cemeteries.

Wreck

Part of the

Titanic wreck in 2003 with

rusticles on it.

The idea of finding the wreck of

Titanic, and even raising the ship from the ocean floor, had been around since shortly after the ship sank.

[j]

Discovery

The most notable finding at the discovery was that the ship had split

apart, the stern section lying 1,970 feet (600 m) from the bow section

and facing opposite directions.

As the ship fell into the depths, the two sections had behaved very

differently. The streamlined bow planed off approximately 2,000 ft

(610 m) below the surface and slowed somewhat, landing relatively

gently. The stern plunged violently to the ocean floor, the hull being

torn apart along the way from massive

implosions

caused by compression of water tight compartments inside the ship. The

stern smashed into the bottom at considerable speed, grinding the hull

deep into the silt.

[177]

Surrounding the wreck was a large debris field with pieces of the

ship, furniture, dinnerware and personal items scattered over 2 square

miles (5.2 km2). Approximately 5,500 artefacts have been removed from the wreck.

Ownership of artefacts

Titanic's rediscovery in 1985 launched a debate over ownership

of the wreck and the valuable items inside. In 1994 RMS Titanic Inc., a

subsidiary of

Premier Exhibitions Inc., was awarded ownership and salvaging rights by the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. (See

Admiralty law)

On 24 March 2009, it was revealed that the fate of 5,900 artefacts

retrieved from the wreck would rest with a U.S. District Judge's

decision.

[181]

The ruling was later issued in two decisions on 12 August 2010 and

15 August 2011. As announced in 2009, the judge ruled that RMS Titanic

Inc. owned the artefacts and her decision dealt with the status of the

wreck as well as establishing a monitoring system to check future

activity upon the wreck site.

[182]

On 12 August 2010, Judge

Rebecca Beach Smith

granted RMS Titanic, Inc. fair market value for the artefacts but

deferred ruling on their ownership and the conditions for their

preservation, possible disposition and exhibition until a further

decision could be reached.

[183] On 15 August 2011, Judge Smith granted title to thousands of artefacts from the

Titanic

that RMS Titanic Inc., did not already own under a French court

decision concerning the first group of salvaged artefacts to RMS Titanic

Inc., subject to a detailed list of conditions concerning preservation

and disposition of the items.

[184] The artefacts can be sold only to a company that would abide by the lengthy list of conditions and restrictions.

[184] RMS Titanic Inc. can profit from the artefacts through exhibiting them.

[184]

Legacy

Literature

In literature, "down like the

Titanic" is a simile that refers to an

epic failure, as does practically any reference to the ship or its sinking. The maritime principle that a

captain goes down with his ship is often made in reference to the

Titanic

and to Captain Smith who practised this. Although the "band playing

while the ship sinks" motif dates back at least to the 1852 sinking of

the

HMS Birkenhead, "while the band played" refers almost exclusively to the

Titanic.

[citation needed]

Films

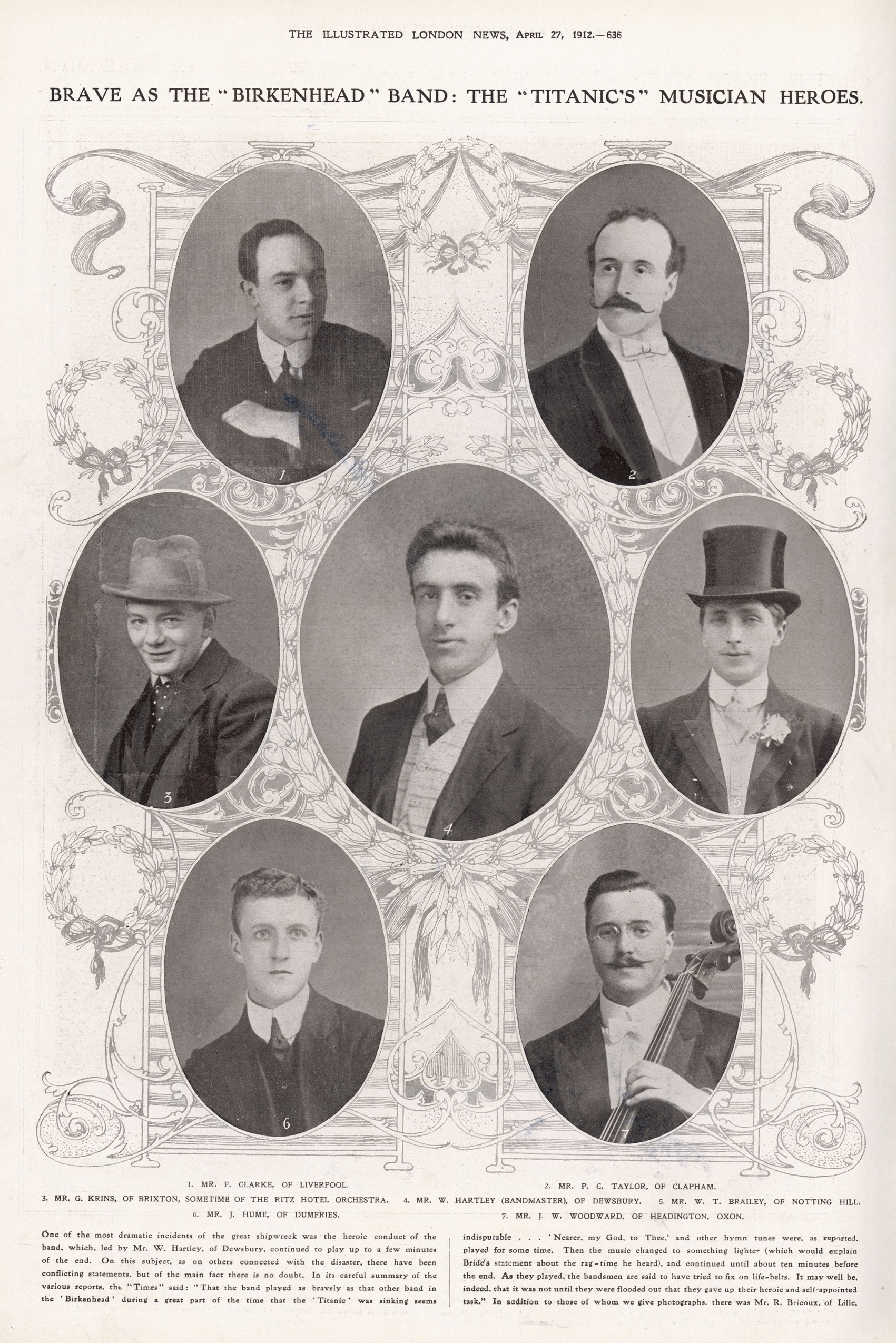

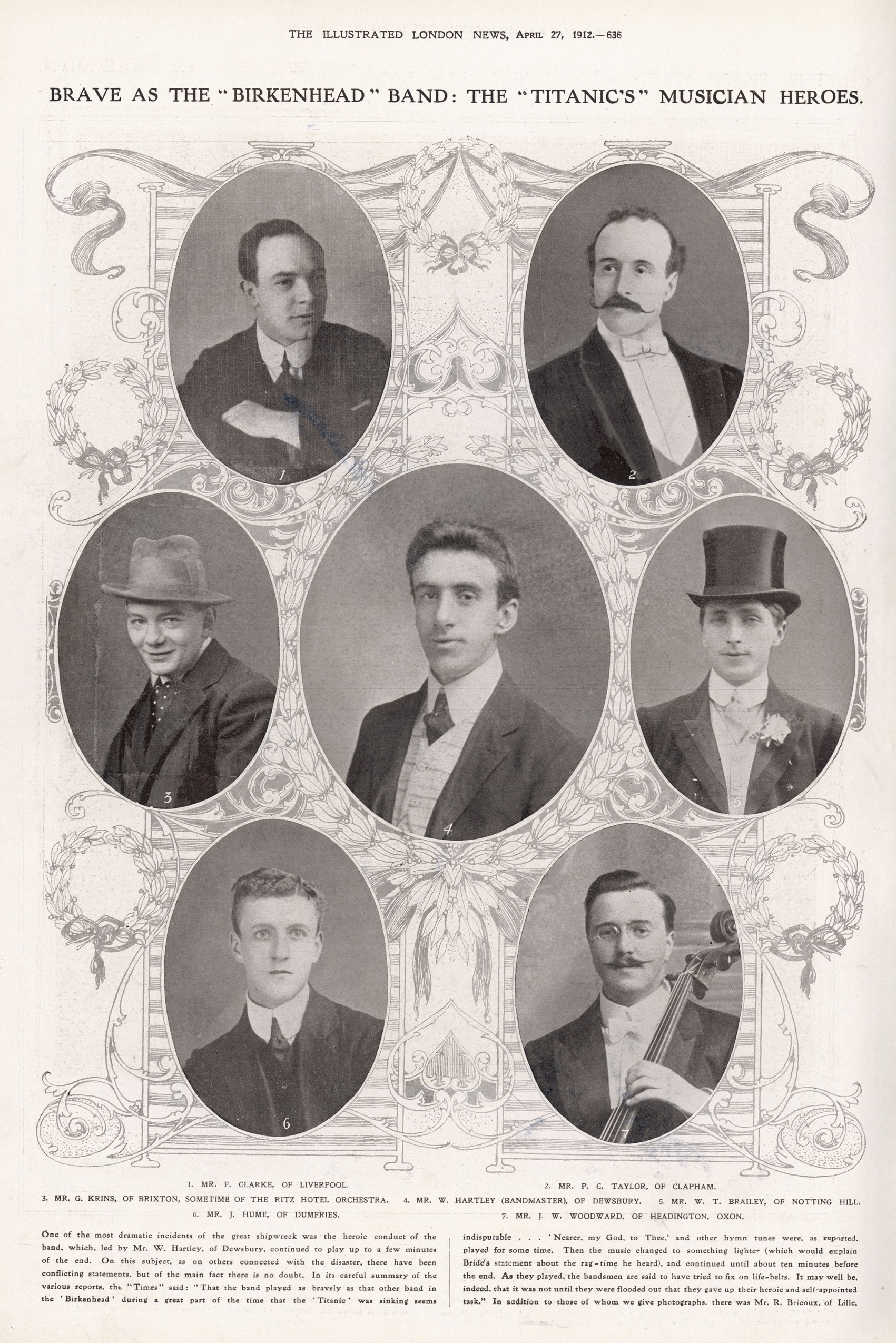

Seven of the eight members of

Titanic's band that became a legend.

Legends and myths

The

Titanic has gone down in history as the ship that was called unsinkable.

[k] However, even though she was called so in news stories after the sinking, the fact is that neither

The White Star Line nor

Harland and Wolff declared her unsinkable.

[191]

Another well-known story is that of the ship's band, who heroically

played on while the great steamer was sinking. This seems to be true but

there has been conflicting information about which song was the last to

be heard. The most reported is "

Nearer, My God, to Thee" but also "Autumn" has been mentioned.

[l] Finally, a widespread myth is that the internationally recognised

Morse code distress signal "

SOS" was first put to use when the

Titanic

sank. While it is true that British wireless operators rarely used the

"SOS" signal at the time, preferring the older "CQD" code, "SOS" had

been used internationally since 1908. The first wireless operator on

Titanic,

Jack Phillips, sent both "SOS" and "CQD" as distress calls.

Memorials and museums

The memorial to

Titanic's engineers in

Southampton unveiled 1914

In

Cobh (formerly known as Queenstown from 1849 to 1920), County

Cork, Ireland a memorial to the

Titanic stands in the town centre.

[195] Queenstown was the final port of call for the ill-fated liner as she set out across the Atlantic on 11 April 1912.

There is a memorial to Bandmaster Wallace Hartley in his home town of Colne in Lancashire.

[197]

A memorial to the liner is also located on the grounds of City Hall in

Belfast,

Northern Ireland.

[198] Titanic Belfast,

a £77m tourist attraction on the regenerated site of the Harland and

Wolff shipyard is to be completed by 15 April 2012, the

100th anniversary of the sinking of

Titanic. The building and surrounding park will celebrate

Titanic and her links with Belfast, where the ship was built.

[199]

The oldest Titanic Museum in America is in Indian Orchard,

Massachusetts. Established in 1963, the Titanic Historical Society

Museum

[202]

houses a number of original artefacts from the ship, including the

lifejacket of Mrs. John Jacob Astor, assorted blueprints, and other

memorabilia. The museum and its co-run Titanic Historical Society,

occasionally loan artefacts to larger museums elsewhere in the United

States.

[citation needed]

Many artefacts are on display at the

National Maritime Museum in

Greenwich, England, and later as part of a travelling museum exhibit. The

Merseyside Maritime Museum in the

Titanic's

home port of Liverpool also has an extensive collection of artefacts

from the wreck located within a permanent exhibition named 'Titanic,

Lusitania and the Forgotten Empress'.

[203] Much floating wreckage which was recovered with the bodies in 1912 can be seen today in the

Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax. Other pieces are part of the travelling exhibition,

Titanic: The Artifact Exhibition.

[204] A newer attraction, the

Branson Titanic Museum opened 2006 in Missouri, USA, is a permanent two-story museum shaped like the RMS

Titanic. It is built half-scale to the original and holds 400 pre-discovery artefacts in twenty galleries.

[citation needed]

100th anniversary commemoration

At 12:13 pm on 31 May 2011, exactly 100 years after

Titanic rolled down her slipway, a single

flare

was fired over Belfast's docklands in commemoration. All boats in the

area around the Harland and Wolff shipyard then sounded their horns and

the assembled crowd applauded for exactly 62 seconds, the time it had

originally taken for the liner to roll down the slipway in 1911.

[205] On 6 April 2012, the 100th anniversary of Titanic's maiden voyage will be celebrated by re-releasing the 1997 feature film

Titanic in 3D.

[206] ITV1 have produced a four-part

Titanic mini-series, written by Oscar-winner

Julian Fellowes, to be broadcast in early 2012.

[207] A new original stageplay by Chris Burgess about the Titanic, called

Iceberg - Right Ahead! will be performed

Upstairs at the Gatehouse from 22nd March - 22nd April 2012.

[citation needed]

The cruise ship

Balmoral, operated by

Fred Olsen Cruise Lines has been chartered by Miles Morgan Travel to follow the original route of

Titanic, intending to stop over the point on the sea bed where she rests on 15 April 2012.

[209]